I was recently asked by a customer to perform a review of their OCI tenancy, following the principle of least privilege I stepped them through the process of creating a user account that granted me read-only access to their tenancy, meaning that I can see how everything has been setup, but I cannot change anything.

Following Scott Hanselman’s guidance of preserving keystrokes I thought I’d document the process here as I’ll no doubt need to guide somebody else through this in the future 😀.

The three steps to do this are below👇

Step 1 – Create a user account for the user 👩

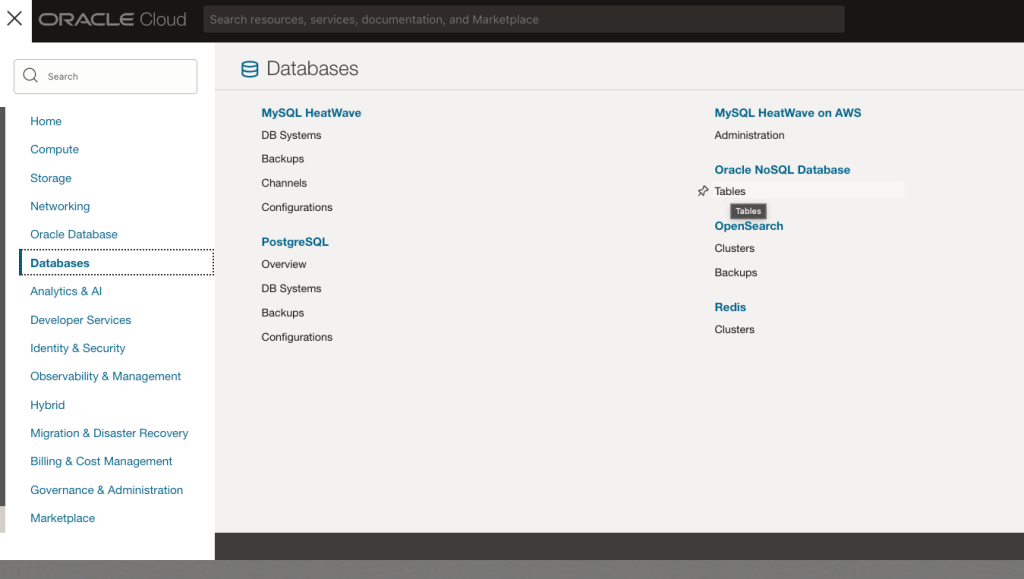

Yes, I know that this is obvious however I’ve included it here for completeness 😜. A user can be added to an OCI tenancy via Identity & Security > Domains > (Domain) > Users > Create user.

Ensure that the email address for the user is valid as this will be used to confirm their account. The user does not need to be added to any groups at this point (we’ll do that in the next step).

If the user who you need to grant read-only access to the tenancy already exists, this step can be skipped.

Step 2 – Create a group 👨👩

OCI policies do not permit assigning permissions directly to a user, so we will create a group which will be assigned read-only permissions to the tenancy.

A group can be created via Identity & Security > Domains > (Domain) > Groups > Create group. I used the imaginative name of Read-Only for the group in the example below.

Once a group has been created, add the user that you wish to grant read-only permissions to the tenancy (in this case Harrison):

Step 3 – Create a policy to grant read-only access to the tenancy 📃

We are nearly there, the penultimate step is to create a policy that grant the group named Read-Only with read permissions to the tenancy, a policy can be created via Identity & Security > Policies > Create Policy.

I created a policy within the root compartment of the tenancy (which targets the policy at the entire tenancy).

I used the following policy statement – allow group Read-Only to read all-resources in tenancy

One thing to note, if you have multiple domains within the tenancy and the user account you wish to give read-only access to the tenancy doesn’t reside within the default domain, you’ll need to specify the domain within the policy, in the example above if the user was a member of the domain CorpDomain, the policy statement should be updated to read as follows:

Allow group ‘CorpDomain’/’Read-Only’ to read all resources in tenancy