I’ve previously used a Power Automate Flow to write responses from a Microsoft Forms survey directly to a SharePoint list – this makes it a little easier to analyse responses than using the native capabilities within Forms or exporting to an Excel file, particularly if you use Power BI as you can connect directly to the SharePoint list to analyse the data collected.

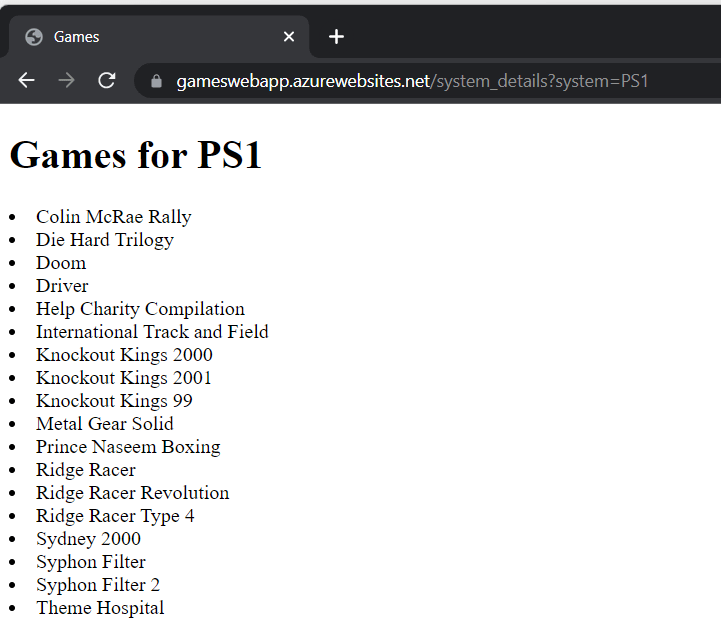

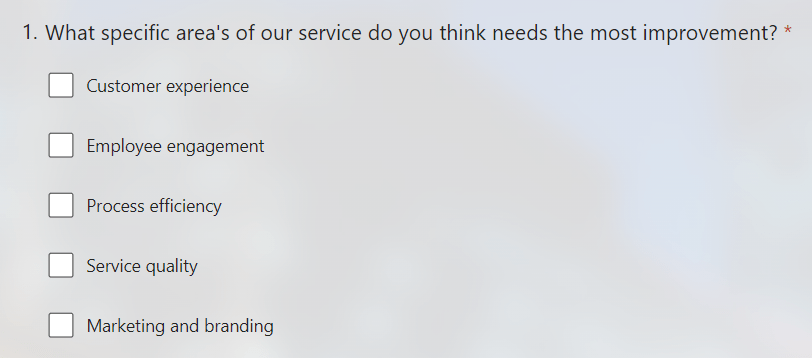

I recently had a situation where I had created a survey that had a question that permitted multiple answers, example below:

The SharePoint list that the responses were written to was configured with a field for this question which used a choice field (that covered each option within the question).

The problem I ran into, is that when multiple answers were passed to the SharePoint list using the Flow these were written as a string and didn’t use the choice field correctly – which looked ugly and made filtering the data difficult.

With some minor tweaks to the Flow I was able to correctly pass the answers to SharePoint and use the choice fields, here is how I did it:

Firstly, here’s the logical flow of the Flow (did you see what I did there 😂):

I needed to add three additional steps (actions) between Get response details and Create item:

1. Initialize Variable

This creates an array variable named AreaChoiceValue which we will populate later with the answers.

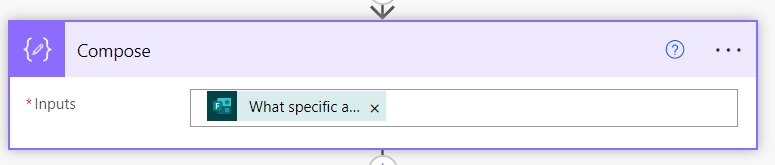

2. Compose

This takes the input from the question that allows multiple answers.

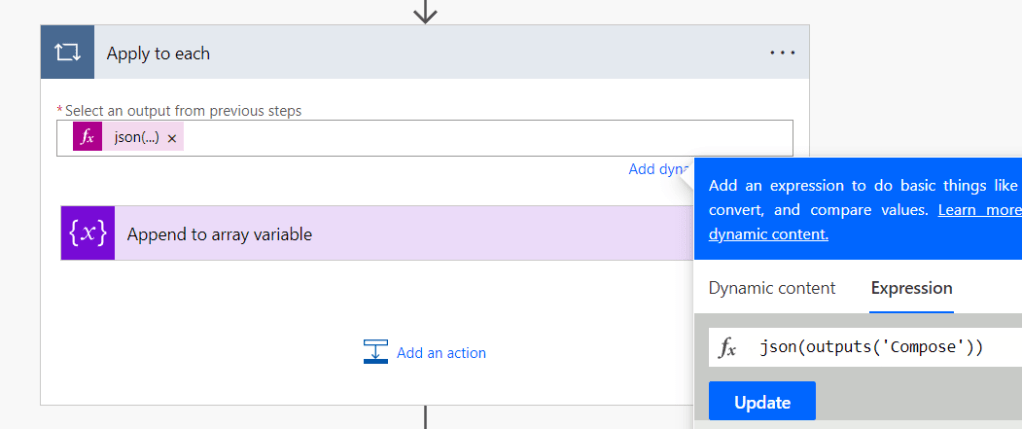

3. Apply to each

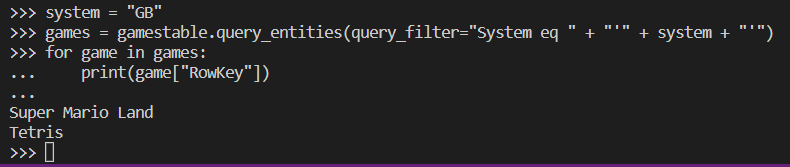

This uses the following JSON function to retrieve the output from the Compose step above – the answer(s) to the question.

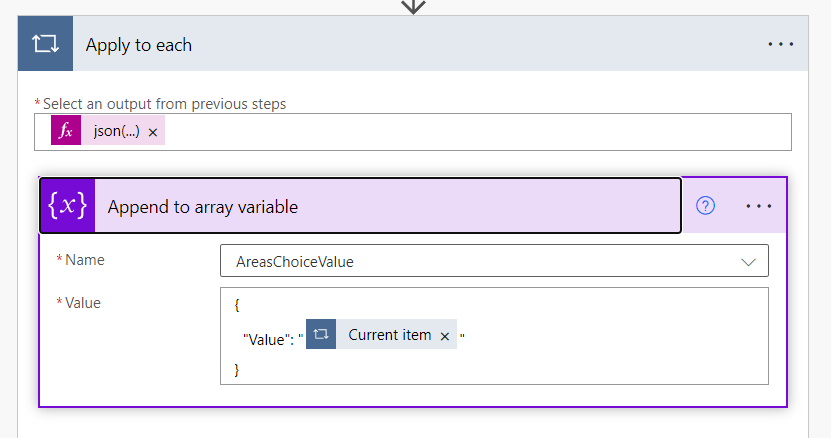

Finally within this block we add Append to array variable using the following format/syntax and referencing the AreasChoiceValue variable created in Step 1:

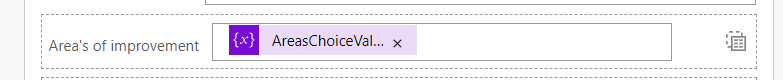

This loops through each of the answers to the question and adds them to the AreaChoiceValue array. Which we can then reference in the SharePoint Create item action:

The choice value is then correctly populated in my SharePoint list:

If you have more than one question that permits multiple answers, you can repeat this within the same Flow (with different variables).

Hopefully this saves somebody some time and frustration.